REVIEW: Olivia Rodrigo is Just a Girl, and That's What Makes Her Great

WHEN SHE CATAPULTED TO STARDOM IN 2021 — Olivia Rodrigo and her debut album, SOUR, were the only things girls could talk about. A popular sentiment was that older girls — mainly 20-somethings who wade in the dark matter that is not quite Gen Z, not quite millennial — wished they had Rodrigo to guide them through the throes of adolescence. Many fought back, arguing their right to claim Avril Lavigne, Hayley Williams, and the rest of the early 2000s pop-rock canon.

When I was eight years old, the only thing I listened to was Miley Cyrus’ Breakout. She was only 16 at the time, and, as the title of her sophomore album suggests, it was a crucial marker of the realization of her voice as an artist. Though I was half her age, I resonated with the seething, mysterious, and angsty tone of her songs. Now, at 23, I’m a bit older than Rodrigo, yet I still feel perfectly aligned with her demographic.

Ever heard the saying “I’m just a teenage girl in a 23-year-old’s body?” It’s the most logical explanation to my emotional reaction when Rodrigo sings, “They all say that it gets better / But what if I don’t?” on “teenage dream,” the closer to her sophomore album, GUTS, released last Friday.

GUTS was one of the most anticipated albums of the year and put a particularly hot beam of light on Rodrigo from music critics’ magnifying glasses. SOUR made it very clear that, with or without Rodrigo’s permission, she was the next great pop star.

Pop music arguably hasn’t had this prophetic of a star since Ariana Grande when she debuted in 2013. But Rodrigo is a very different pop star, in that she’s not so different from the rest of us. She is an acute representation of everything the youth is today: She’s angry, she’s witty, and she bites back.

I already see Rodrigo as a musician and celebrity going through the tired motions that other great pop stars went through before her. Immediately after GUTS dropped, everyone chimed in with their two cents. One X (formerly Twitter) user said, “sorry i will not be listening to olivia rodrigo because i am a tax-paying adult.” Another shared, “olivia rodrigo album is for the nice girl you knew in high school who said she had an emo phase when in reality she just liked paramore.”

Even taken simply as jokes, they suggest two things (actually, they suggest much more than two, but I’ll focus on these). One, that Rodrigo’s material is meant only for “little girls,” and two, that despite her emo and punk influences, her music is for girls who are probably just posers.

Three years into her career and Rodrigo is already being met with downcast looks by many. But this isn’t new — society not taking young, female pop stars seriously is a tale as old as time. We’re lucky to live in a pop-rock comeback era in which artists such as Lavigne and Williams are retrospectively given their well-deserved respect and praise, but there was a time when they too were shrugged off.

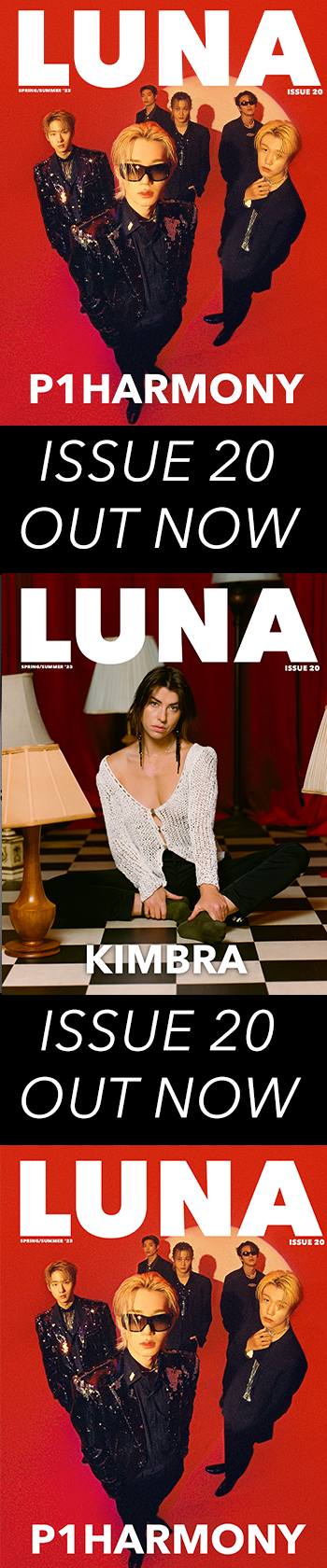

Photo by Larissa Hoffman

In 2002, a Rolling Stone reporter called Lavigne’s Let Go gimmicky, and suggested that if her voice wasn’t as powerful as it was, the record wouldn’t have mattered at all. In 2007, NME called Paramore’s RIOT! “ridiculously misjudged,” a “cynical bid for the mainstream” (namely, not “emo” enough).

The mainstream downplays the reality of a woman’s anger so much that it’s nearing a desensitized topic. To minimize the risk of reducing this genre of music to something too obvious, like “angry girl music of the indie-rock persuasion,” it's important to note that Rodrigo and those who walked before her have much more nuance to their music than anger.

It’s too easy to call GUTS an angry album. Of course it is — I have no doubt that Rodrigo was pissed off when she came up with the “bloodsucker / fame-fucker” quip (“vampire”) or the sardonic “I don’t get angry when I’m pissed” (“all-american bitch”). The singer-songwriter knowingly revels in delusion on most tracks. She is toxic on “bad idea, right?” when she turns her location off and sneaks in through her ex’s apartment window — “Fuck it, it’s fine,” she sings. She gives Bob the Builder energy on “get him back!” when she wants to ruin a guy just to fix him.

And sometimes the anger is a reflection. “Ballad of a homeschool girl” explores the experience of acting weird in public and how it makes you want to die. “Lacy” depicts how we see God in the eyes of pretty girls we like, even if they’re just regular people. Perhaps this introspection is summed up best on “love is embarrassing:” “Love’s fucking embarrassing / Just watch as I crucify myself.”

All of GUTS is in tune to that beloved 2000s pop-era that Rodrigo is somewhat indebted to. It seems like the grungy spitter that is SOUR’s opener, “brutal,” opened her eyes to what she wanted to home in on her next record. But it’s not enough to prize GUTS on how much it sounds like an album that could’ve been released in 2002. The similarities it shares with our nostalgic idols is not alone in what makes the sophomore LP an important record.

When Phoebe Bridgers interviewed Rodrigo for Interview Magazine, Bridgers reflected, “I think the reason you speak to young people is because you fucking take them seriously.” And that’s the heart of what makes GUTS a worthy follow-up to SOUR, and overall what proves Rodrigo to be a diamond in the rough of the too-wide world of modern pop.

When Rodrigo is a toxic, “delulu” girly pop on GUTS, someone in Gen Z would likely call it meta. It’s not healthy or mature to willingly be either of those things, and that’s exactly why we do it. Sometimes it’s intentional, because then at least we’re in control of our narrative, whether it’s delusional or not.

When feeling like a normal and well-adjusted human being feels impossible, it’s much easier to be weird and insane. We revel in irresponsibility, solely because it’s easier that way. At some point, you have to decide when to snap out of it.

In the GUTS timeline, it’s back and forth. One of the album’s most sincere tracks is “making the bed.” In it, Rodrigo lists perhaps too many of her flaws for comfort, a number that most people would never admit to or be self-aware enough to recognize. But Rodrigo is smart, and people don’t highlight her maturity just to flatter her.

When I listen to Rodrigo sing about her personal downfalls, how embarrassed she is to be alive, the pent-up air in my lungs collapses in relief. There’s comfort in knowing that someone we praise as the next voice of our generation is in her position because she’s just like everyone else. The reason both 16- and 23-year-olds alike relate to a 20-year-old Rodrigo is because we’re all just Sisyphus pushing the same rock up the same hill. Everyone is a teenage girl.